Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

You look around your business and see

0:02

inefficiency everywhere. So you should know

0:04

these numbers. The

0:07

number of businesses which have upgraded to

0:09

the number one cloud financial system. NetSuite

0:12

by Oracle. NetSuite

0:15

just turned 25. That's

0:18

25 years of helping businesses streamline

0:20

their finances and reduce costs.

0:23

One, because your unique business

0:25

deserves a customized solution, and that's

0:28

NetSuite. Learn more when

0:30

you download NetSuite's popular KPI

0:32

checklist absolutely free at

0:36

netsuite.com/reveal. That's

0:38

netsuite.com/reveal.

0:42

From the Center for Investigative Reporting

0:44

and PRX, this is Reveal. I'm

0:47

Al Ledson. Today, we're going

0:49

back in time to a

0:51

moment when a deadly virus was

0:53

spreading in America. No,

0:55

not the coronavirus. Think a

0:57

few decades earlier. It's

0:59

morning again in America. Today,

1:03

more men and women will go to work than ever

1:05

before in our country's history. It's the

1:07

early 1980s, and Ronald Reagan

1:09

has just been elected president on the

1:11

promise that better days were ahead for

1:14

this country. This famous

1:16

campaign ad said it all. This

1:18

afternoon, 6,500 young men and women

1:20

will be married. We can all

1:22

prosper if we agree to look

1:24

away. To look away from

1:26

the hard stuff, and instead to look

1:28

ahead. And with inflation of less than

1:30

half of what it was just four years ago, they

1:34

can look forward with confidence to the future.

1:37

Except that at the same time, a

1:40

mystery illness was spreading that

1:42

completely confounded scientists, AIDS.

1:46

The disease killed tens of

1:48

millions, and people are still

1:50

dying. It's torn apart families

1:52

and communities and whole nations. It

1:55

is hung as a permanent cloud

1:57

over intimacy, love, and lust for

1:59

generations. and to this day

2:02

when most people think of AIDS they think

2:04

about gay men. But according

2:06

to Kye Wright, host of

2:08

WNYC's Notes from America and

2:10

Lizzie Ratner, the nation magazine's

2:13

deputy editor, that oversimplification

2:15

that AIDS is a gay

2:17

disease is a dangerous one. They've

2:20

created a series called Blind Spot, The

2:22

Plague in the Shadows. It's

2:24

a collaboration between the History Channel

2:27

and WNYC and it looks at

2:29

the early days of AIDS and

2:31

how entire segments of American society

2:34

were overlooked by researchers and policymakers

2:37

and what that's meant for the people who

2:39

are ignored. Here's Kye. The

2:43

virus announced its presence to mainstream America

2:45

in an article that appeared in the

2:47

back pages of the New York Times.

2:49

There was a single column story. If I

2:52

recall correctly it was page 820. I don't

2:55

remember how many pages there were. A story

2:58

published on July 3rd 1981

3:01

written by the OG of

3:03

medical journalism. I am

3:05

Dr. Lawrence K. Altman, a

3:08

former science writer and columnist

3:10

for the New York Times

3:13

and covered medicine for the

3:15

New York Times for nearly

3:18

50 years. Larry

3:21

Altman's July 1981 article

3:23

is often called the first media report on

3:25

what would become known as AIDS. That's

3:28

not true. The gay press had already

3:30

begun talking about an odd series of

3:32

illnesses that were showing up in the

3:34

community and there had been coverage in

3:36

California newspapers as well. But

3:38

certainly Altman's article in the New

3:40

York Times was a defining moment.

3:43

It broke the news to the widest audience,

3:45

made it a real thing and the way

3:47

only a New York Times article can do.

3:51

The headline read rare cancer

3:53

seen in 41 homosexuals. Outbreak

3:56

occurs among men in New York

3:58

and California. Eight

4:00

died inside two years. And

4:03

then the story began. Doctors

4:06

in New York and California have

4:09

diagnosed among homosexual men 41

4:12

cases of a rare and often rapidly

4:15

fatal form of cancer. Now,

4:17

Larry Altman is writing here as

4:19

a kind of split personality, as

4:21

a reporter, but also a

4:23

doctor who practices and sees patients.

4:25

As a physician, I had

4:28

time to do medicine, take

4:30

time from the times to do that.

4:32

And as a doctor, his focus is

4:34

infectious disease, which is why

4:37

his antenna is up about

4:39

this so-called cancer. Over

4:42

the previous month, Altman had read

4:44

two notices about it and a

4:46

publication called the Morbidity and Mortality

4:48

Weekly Report, or the MMWR. That

4:51

wonky name is appropriate. It's kind

4:53

of a biz-de-biz trade publication, but

4:55

for public health. It's

4:57

what the federal government uses to update

5:00

local health departments and doctors in

5:02

real time about emerging trends. Some

5:06

doctors who were practicing in cities

5:08

with big gay populations, they noticed

5:10

all these young men suddenly getting

5:12

sick. They didn't know exactly

5:14

what they were seeing, but right away, they

5:16

put it in the MMWR. Heads

5:19

up, everybody. Something's happening. We don't know

5:21

what it is yet, but here's what

5:23

it looks like, and let's call it

5:25

a cancer for the time being. And

5:28

now, when Larry Altman read about

5:30

these symptoms, they sounded really familiar.

5:33

He had practice medicine at Bellevue, which is

5:35

a public hospital that treats a lot of

5:37

poor patients. And he says

5:40

he'd been seeing these symptoms there since at

5:42

least the late 70s. And

5:44

we couldn't determine the cause, and

5:47

we'd work in the medical

5:49

jargon. We'd work up every case to the

5:51

Hill, doing all the tests

5:53

we knew how to do, and

5:56

still not being able to determine

5:58

what they had. We knew what

6:01

they didn't have, but we didn't know what they

6:03

had. And when we went back and looked, it

6:06

was clear that they had what we now know

6:08

as AIDS. At

6:10

this stage, people weren't

6:12

seeing beyond gay men. What

6:16

about yourself? What were you seeing at that

6:19

time? I mean, the report you wrote was

6:21

about the 41 men. Could

6:23

you see more than that? Yes,

6:26

because I had the experience at Bellevue,

6:29

and we had women who had

6:31

been former IV drug users, or

6:33

injecting drug users. And

6:36

they had the same generalized swollen

6:39

lymph nodes that men had.

6:42

So to me, I

6:44

didn't see that it would be limited to

6:48

the gay men population.

6:54

But that's not what he reported.

6:56

So I asked him why he didn't write about what

6:58

he was seeing in the newspaper. What

7:01

do you think if in the newsroom of 1981,

7:03

if you had said, no, I can see it's

7:05

more than these 41 gay men, and

7:12

I want to write about women who are

7:14

drug addicted that I've seen in the past?

7:17

And I mean, how do you think that

7:19

would have been received amongst her editors? I

7:23

think they would have to want to

7:25

know how that fit into a bigger

7:27

picture. Was this just

7:29

an oddity? And

7:32

if it's an oddity, I don't think the Times

7:34

would have been interested. If you could show that

7:36

it was part of a broader pattern, then

7:39

they presumably would have been

7:41

interested. But we didn't have the evidence

7:43

in. Nobody was reporting it. There

7:46

was no data reported. So

7:49

yes, it would be in my mind. But

7:54

we weren't reporting theory. We were trying

7:56

to report the facts of what was

7:58

known. And

8:03

the facts were coming from

8:05

the MMWR, which focused only

8:07

on gay men. Do

8:13

you wrestle at all with the

8:17

limitation of reporting

8:19

on what the

8:21

CDC is establishing

8:24

versus being able to raise

8:26

questions about what you were

8:28

seeing at Bellevue that you

8:31

couldn't quite prove, but that you

8:33

were like, something else is going on here too? We

8:42

weren't writing personal opinion. We

8:45

were reporters. I was a reporter. That

8:48

kind of journalism didn't exist at that time.

8:51

I wasn't writing using the

8:54

word I and writing first-person

8:56

accounts. It was coming

8:58

off the news and explaining

9:02

what was going on. Larry

9:14

Altman's 1981 article was

9:16

just one link in a really

9:18

consequential feedback loop that locked into

9:21

place over the first year or

9:23

so of this as yet unnamed

9:25

epidemic. Each time

9:27

there was another public comment about

9:30

the gay cancer, doctors who treated

9:32

gay men would call the CDC

9:34

and say, Hey, I have seen

9:36

this too. And this is

9:38

a good thing. The whole point was to find more

9:40

cases, but it also

9:42

steadily narrowed the focus onto

9:44

who was affected rather

9:47

than what was happening. People

9:49

were looking where it was easy for them to

9:51

look. I've

10:00

known him for decades and worked with him for

10:02

many years. And ever

10:04

since the mid-80s, he's been begging

10:06

people to see this epidemic in

10:08

broader terms. You probably

10:11

heard me tell the story about the

10:13

guy who loses his keys. So

10:15

he loses his keys and he's looking and he's looking and he's

10:17

looking for his keys and he can't find his keys. And another

10:19

guy comes up and he says, what are you doing? He says,

10:21

I lost my keys. And the guy

10:23

says, well, where were you the last time you

10:25

saw your keys? And the guy says, about a

10:28

block down the road. And the guy says, well,

10:30

why are you looking here? And he says, because

10:32

the lights better. And

10:35

so basically that's how we were

10:38

developing narratives. Most

10:45

people thought about this as, well,

10:47

it's just a gay disease, you know,

10:49

so we don't need to worry about

10:52

it. It's somebody else's problem. This

10:54

is Tony Fauci. Yes, of COVID

10:56

fame. Fauci was head

10:58

of the federal agency that leads

11:00

research on infectious diseases for almost

11:02

40 years. And

11:05

so his first public notoriety came as

11:07

the federal point person on AIDS. He

11:10

was at the scientific front line from the start,

11:12

which means he's been rehashing what

11:15

went right and what went wrong

11:17

for decades, including this narrow focus

11:19

on gay men at the outset.

11:22

I see where you were going. And

11:25

he argues, look, you got to

11:27

remember that this was an unprecedented

11:29

epidemic. When you're dealing with a

11:32

new disease, it unfolds

11:34

in front of you in real

11:36

time. And what you know, like

11:39

in June and July

11:41

of 81, is very different from

11:44

what you learned in 82, very

11:46

different from what you learned in 83. And

11:50

very different than what we

11:52

understand now, 40 some odd

11:54

years later. We experienced this

11:56

as recently as COVID-19. When

12:01

the first cases that came out, it

12:03

wasn't appreciated, but it was very

12:06

easily transmitted from human to human. It

12:08

thought it was like a very inefficient.

12:11

Then after a few weeks to a month, we found

12:13

out it was transmitted

12:15

extremely efficiently. So what

12:18

it means is that you're dealing with

12:20

a moving target. And

12:22

when you finally get enough information,

12:25

you look back and you say, wow,

12:28

how long did it take the

12:30

general population, the

12:32

public health population, and other

12:35

people to realize that

12:37

the target was moving and

12:40

expanding. As

12:45

for AIDS, here's what was officially known about

12:47

the epidemic in the United States by the

12:50

end of 1981. There

12:53

were 337 reported cases of people

12:55

experiencing a sudden collapse of their

12:57

immune systems. One hundred and

12:59

thirty of those people were already dead. For

13:02

the cases in which a person's sexual orientation was

13:04

known, a report that summer

13:07

found more than 90 percent were

13:09

gay or bisexual men, almost exclusively

13:11

in a few big coastal cities.

13:14

We now know for certain that the

13:17

epidemic was far wider than gay men

13:19

already, an estimated 42,000

13:22

people were living with HIV in the US

13:24

alone. For

13:27

at least the first couple of years

13:29

after that MMWR and Larry Altman's New

13:31

York Times article, that's

13:33

where the public conversation began and ended.

13:37

A mystery disease known as the gay

13:39

plague has become an epidemic unprecedented in

13:41

the history of American medicine. It's

13:43

mysterious, it's deadly, and it's

13:45

baffling medical science. For disease

13:47

control in Atlanta, topping the list

13:49

of likely victims are male homosexuals who

13:51

have many partners. Which meant

13:54

if you didn't consider yourself part

13:56

of that group, you saw no

13:58

reason. for this

14:00

new health scare to interrupt your morning

14:03

in America. And even

14:05

among gay men, you had

14:07

to be a certain kind of homosexual for

14:09

this to be your problem. But

14:13

it wasn't just the gay men's problem. It

14:16

was women. It was black people,

14:18

heterosexuals. It was Latinos. It was

14:20

children. Aids did not

14:22

discriminate. When we

14:25

come back, more voices from the

14:27

podcast Blindspot, The Plague and the

14:29

Shadows. We literally

14:31

had to convince the federal

14:33

government that there were women

14:35

getting HIV. We actually

14:38

had to develop treatment and

14:40

research agendas that were about women.

14:43

How women struggle to be seen as victims

14:45

of the deadly disease. You're

14:48

listening to Reveal. From

14:57

the Center for Investigative Reporting in

14:59

PRX, this is Reveal. I'm

15:01

Al Ledson. This

15:04

episode, we're bringing you stories from

15:06

the early days of AIDS and

15:08

the fight to get policy makers

15:10

to pay attention to communities that

15:12

were hit hardest. It's

15:14

from a podcast series called Blindspot,

15:16

The Plague and the Shadows. By

15:19

the late 1980s and the early

15:22

90s, a surge of activism had begun

15:24

to make progress on AIDS. Public

15:26

awareness was growing and elected officials could

15:29

no longer ignore it. In

15:31

1990, Congress passed the Ryan White Care

15:33

Act, which provided over $200 million

15:36

in its first year to fund

15:38

care and treatment for low-income people

15:41

living with HIV. It

15:43

was an enormous milestone, but

15:45

one that overlooked an important group of

15:48

people. Lizzie Ratner from The

15:50

Nation magazine explains. the

16:00

funding that was going to fight the disease,

16:03

there were a bunch of people who were

16:05

being left out. Women. Studies

16:08

on HIV and AIDS, clinical trials

16:10

to test new treatments, medical

16:13

conferences, those were all

16:15

about men. And the very

16:17

definition of AIDS itself didn't

16:20

include symptoms that were being

16:22

experienced specifically by women. This

16:26

story begins inside a maximum security prison

16:28

for women. We were these supposedly criminals,

16:30

you know, the outcast of society that

16:33

was responding to the epidemic in a

16:35

way that some communities out here were

16:37

not even responding. And that really made

16:40

us hyped. One

16:42

name kept coming up at the center of this

16:44

story. Katrina. Katrina. I kind

16:46

of became obsessed with who is Katrina

16:49

Hassel. Katrina was

16:51

an inspiration to all Katrina

16:56

has. She was only in her 20s

16:58

when she arrived at the Bedford

17:00

Hills Correctional Facility. She

17:02

grew up in Niagara Falls, one of 11 kids.

17:05

In her late teens, she found Islam

17:07

and married a religious man and moved

17:09

to Brooklyn. But

17:11

by the age of 21, she moved back

17:14

to Niagara Falls and fallen pretty deep

17:16

into an addiction to heroin. She

17:18

could stay out on the streets all night and

17:21

still somehow managed to go to college

17:23

in the morning. She

17:26

soon started doing sex work and stealing. And

17:28

the word was that she could lift a

17:30

wallet off of anyone. She

17:33

ended up getting arrested for pulling a knife on

17:35

a client. And that is how in 1985, she

17:37

ended up in a maximum security prison for

17:40

women in upstate New York. Katrina

17:46

was very fiery. And she had

17:48

a real temper. Judith

17:51

Clark. She met Katrina

17:53

in solitary confinement, the prisons

17:55

prison at Bedford Hills. I

17:58

think she got into a scuffle with officer

18:00

is my memory of what led

18:02

her there. And I remember saying,

18:04

you know, saying something like, Oh God, it

18:07

was worth it. Oh my

18:09

God. It was this great big smile

18:11

on her face. Judy

18:14

was also in prison at Bedford and

18:16

the crime that got her there, it was

18:19

a big deal. Good

18:22

evening. Echoes of the violent radical

18:24

underground of the 1960s rolled over the New

18:27

York suburb of Nanyuet today in

18:29

the botched ambush of an armored car

18:32

that left one guard and two policemen

18:34

dead. The Brinks

18:36

robbery. It was a crime

18:38

committed by an offshoot of the far

18:41

left weather underground. Three people were killed.

18:43

Judy was driving the getaway car and she

18:46

and Kathy Boudin were among the four people

18:48

arrested. Judy was sentenced

18:50

to 75 years to life in prison.

18:56

Our cells were very bare, you

18:59

know, cinderblock walls and

19:01

a solid door and then a

19:04

small window on the

19:06

other side that had a lot of mesh

19:08

on it. I

19:10

mean, it sounds kind of terrifying. It was.

19:13

In solitary confinement,

19:15

they were allowed just one hour

19:17

a day outside. And

19:19

most days, Judy would walk laps around

19:22

the track alone. And

19:24

then after a few months,

19:26

suddenly this

19:28

woman appears. She's

19:31

beautiful and very

19:33

elegant. She wore a head

19:35

wrap. She wore a long

19:37

dress and it was incredibly

19:39

stylish. There are

19:41

people who managed to be stylish in prison

19:43

and Katrina was one of them. And

19:48

something between the two women clicked.

19:51

They were both grappling with their lives

19:54

before prison, what they had done. And

19:56

so every day they would walk and

19:58

just talk. You She told

20:00

me a little bit about her

20:02

life and about her own struggle toward

20:05

recovery, having gone through a period

20:07

of addiction. On the one

20:09

hand, she's incredibly intelligent. She

20:13

was a practicing Muslim, but

20:15

she had this fire, and

20:17

it could get her in trouble. And

20:21

that is what drew them together and got them

20:24

to start organizing in prison. Let's

20:27

take a look at the issue of AIDS in

20:29

prisons. This is Dr. Sheldon Landesman, and he's speaking

20:31

at a forum in 1987. A

20:34

huge percentage of the persons in the prison

20:36

system, and I can't get a good handle

20:38

on the number anywhere from 70 to 80

20:40

percent, have used drugs prior

20:43

to coming to prison. We know

20:45

from a variety of studies that at a

20:47

minimum, 50 percent of the intravenous drug users

20:49

in the New York City and surrounding area

20:51

are infected with the AIDS virus, taking

20:54

the most conservative estimates. AIDS

20:57

was becoming a huge problem in the prison

20:59

system and not just among injection drug

21:01

users. The New York

21:03

Department of Health tested women as they were

21:05

entering the prison system in It

21:08

found that fully 18.8 percent

21:10

of women tested positive

21:13

for HIV. That is almost one

21:15

in five women, higher than

21:17

the rate for men. In these

21:19

numbers, they were probably an undercount. In

21:21

Bedford, so many women had fallen sick

21:24

and disappeared that rumors were

21:26

running wild. Nobody know

21:28

what the hell was going on. Meet

21:31

Ewilda Gonzalez. Everybody calls

21:33

me Wendy. Wendy

21:35

got to Bedford around the same time as Katrina in 1985.

21:39

She was in for possessing and selling drugs. And

21:42

when she arrived, she found everyone

21:44

on edge. Well, many

21:46

women bullied other women, harassed

21:49

them, beat them, shame

21:52

them, blame them.

21:55

Their own fear because at one point we

21:57

all looking at these women and saying Wait

22:00

a minute. How many times

22:02

did I share a needle? See? But

22:06

how many times do you make love

22:08

to somebody and they didn't tell you

22:10

or they didn't know? There

22:12

was still a lot of confusion around how you

22:15

got HIV, but there was one thing that everybody

22:17

knew. If you got infected,

22:20

you died. I mean, no one

22:22

wants her to be seen going to

22:24

the medical department for anything because they were

22:26

afraid that people would say, oh, she's an

22:29

AIDS bitch. Wendy worked

22:31

as a hairdresser in the prison hair salon,

22:33

and she was starting to get lots and lots

22:36

of questions. My sister is the

22:38

knife that I use to do certain

22:41

styles in the hair, and

22:43

women question me, what are you doing

22:45

to disinfect this? And I say, you

22:47

know what? I need to

22:49

educate myself. Either

22:52

people were going to turn against

22:54

each other, as was happening, or

22:56

people were going to be able

22:58

to seek each other.

23:01

The women started organizing to put together a

23:03

meeting. You didn't have to be HIV positive

23:06

to join. Well, you know,

23:08

we wanted women among the druggies. We

23:10

wanted women among the good old Christians.

23:12

We wanted white women. We wanted Hispanic

23:14

women. We wanted black women. We wanted

23:17

religious. We wanted non-religious. We wanted hippies.

23:20

Katrina was part of that initial organizing

23:22

group. She worked in the law

23:24

library, and so she began spreading the word to

23:27

other women. Soon, they had

23:29

30 people who were interested.

23:32

Here's how she described that first meeting in

23:34

a documentary a few years later. So

23:36

we went around introducing ourselves, and about

23:39

the third woman, she said, my name

23:41

is Sonia, and I have AIDS. And

23:44

I had never heard anybody say that before out

23:46

loud, and I don't think anybody else in the

23:48

room had heard anybody say that out loud. And

23:50

the room went like silence. And

23:52

then people like engulfed her.

23:54

And it made me cry because it was like

23:57

there was so much support in the room. first

24:00

person who was able to say, I have AIDS, you

24:02

know, and I thought to myself, I

24:04

can never say that. Katrina

24:12

had tested positive for HIV a few

24:14

months before this meeting, but she

24:17

was not ready to be public about it. She

24:19

told me, she told

24:22

a couple of other friends, Judy Clark,

24:24

it's sort of all in nothing

24:26

in there. I think really once

24:29

she decided that

24:31

it was too much effort to keep

24:33

it secret and liberated her, like

24:35

she then could have a voice and

24:37

a role and we were

24:39

connected by then to people on the

24:41

outside who were also powerfully

24:44

raging a struggle and she

24:47

loved the idea of that struggle. And

24:49

so I think it gave her a

24:51

sense of purpose and identity that was

24:53

part of her own self liberation. At

24:59

a meeting one day, Katrina got up in front

25:01

of everyone and she told them. And

25:04

people's mouths like dropped, you know, because

25:07

like I say, they see me as this Muslim,

25:09

you know, they see me as, you know, this

25:11

girl who jogs in the yard all the time,

25:14

you know, I was the law library clerk, so

25:16

no, I was straight, you know, so how did

25:18

she get infected, you know? And

25:21

so I said to them, close your mouth. Katrina

25:29

never complained about nothing. She

25:31

would come with her fluoride herself and

25:34

her little notebook, feisty,

25:37

fair, soft spoken.

25:44

Katrina, little

25:47

piece of chocolate, her skin

25:49

was so chocolate

25:51

like, you know, nice and soft.

25:55

Very analytic. While we were all going off,

25:58

she was sitting down listening. Because

26:01

Wendy was a hairdresser, she knew

26:03

everybody. So she was also recruited to

26:05

join the group. We were so blessed

26:07

to really establish something

26:10

to help us survive

26:12

at that time and

26:14

be creative and be productive

26:17

because society forgot about us. Like

26:19

they forget, once you go to prison, that's

26:21

it, especially in maximum

26:23

security. They

26:25

don't care what happened to us, we're

26:27

just dogs. But

26:33

the women, they did care about what happened

26:35

to each other. And so they would talk

26:37

openly in these meetings about their fears and

26:39

their symptoms and how to protect themselves. Here's

26:42

Wendy leading a workshop at the prison in

26:44

Bedford. Okay, so I bring the bill. No,

26:48

it's not. No,

26:50

Rosa, Mileni. Okay,

26:52

and you get the key with the camera

26:54

and we can't do it. We have to

26:56

have the same sexual. She's talking about safe

26:59

sex. No sex. I

27:05

am the greatest sex educator

27:08

ever, honey. By

27:10

this point, the group had a name for

27:12

itself. They called it AIDS Counseling and

27:14

Education, or ACE for short.

27:17

It was the first known AIDS group for

27:19

women in the nation, and it was formed

27:22

in a prison. It

27:24

was the beginning of what would

27:26

become Katrina Haslip's life's work.

27:29

I represent the excluded and

27:31

underrepresented groups of women,

27:33

minorities, and HIV-positive individuals and

27:36

also prisoners, of which I am

27:38

a member of all of the above. Pretty

27:43

soon, people outside of Bedford began

27:45

hearing about Katrina's work. One

27:48

of them was Terri McGovern. She

27:51

founded the HIV Law Project in Lower

27:53

Manhattan. So when these

27:55

women started to come in, a

27:57

number of them had been incarcerated

27:59

at Bedford. Hills and they

28:01

were all talking about this jailhouse lawyer

28:03

who would help them Katrina Haslip and

28:05

whenever they said Katrina Haslip they would

28:08

get these broad smiles so

28:10

I kind of became obsessed with who is Katrina

28:12

Haslip. Terry would

28:14

soon get to find out because it was September

28:16

of 1990 and Katrina was about

28:19

to be released from prison. Judy

28:21

Clark was still inside. She

28:23

was very clear that when she left

28:26

Bedford she was going

28:28

to be part of the movement

28:30

outside. She was going to bring the

28:32

voices of women and black women.

28:35

Katrina would

28:42

do almost anything to get those

28:45

voices out there including breaking her

28:49

parole.

28:52

When we come back more from Blindspot,

28:54

The Plague in the Shadows. You're

28:57

listening to Reveal. We

29:09

start where it began. In the life

29:11

of a captive life never got

29:13

better. From the dungeons in Ghana to

29:15

New England's primary slave port, Boston,

29:17

birthplace of Liberty was also the

29:19

first colony to legalize slavery. As

29:21

our nation struggles with the question

29:23

of reparations we look at how this

29:26

long overdue reckoning is unfolding in

29:28

the city that sparked the American

29:30

Revolution. In GbH News I'm Saraya

29:32

Wintersmith. Join me for what is

29:35

old available wherever you

29:37

get your pen. From

29:42

the Center for Investigative Reporting and

29:44

PRX this is Reveal. I'm Al

29:47

Ledson. Katrina Haslip

29:49

was a prisoner in New York State

29:51

when she helped organize an AIDS group

29:53

for women. She was determined

29:56

to take her advocacy to the national stage

29:58

as soon as she got out. Reporter

30:01

Lizzie Ratner from the podcast Blindspot,

30:03

The Plague in the Shadows, explains

30:05

how Katrina went about doing that.

30:10

On September 10th, 1990, Katrina Hasseliff

30:12

was released from the Bedford Hills Correctional

30:15

Facility. Within three weeks,

30:17

she breaks her parole by taking

30:19

a bus to Washington DC to

30:21

join a massive protest organized

30:24

by ACT UP.

30:29

And there's someone else there, Terry

30:31

McGovern of the HIV Law Project.

30:34

I had been to many ACT UP

30:37

demonstrations but they were never like

30:39

you know predominantly women of color

30:41

with HIV speaking you know

30:43

so it was a different type of demonstration

30:46

for sure. A

30:52

seven-year-old woman with AIDS. One of

30:55

the reasons why women remain untreated is

30:57

because they don't have Medicaid and

31:00

they have no access to healthcare. We

31:03

can't afford it. Terry

31:06

had just submitted a lawsuit that

31:08

dealt with precisely that. She

31:10

was suing the federal government for discrimination.

31:13

Her argument was that the

31:15

government's definition of AIDS left out

31:17

symptoms but affected women. I'm

31:19

Phyllis Sharp from New York. I'm

31:21

also a plaintiff in this lawsuit

31:23

against the Social Security in

31:26

2019 to see how it's

31:28

been done. It's hard to

31:31

change the definition of killing

31:33

women and

31:35

I love that disability. Thank you.

31:45

And then suddenly somebody said Katrina Haslip is

31:47

getting off the bus. Terry

31:49

and Katrina had never actually met

31:51

before in person and I

31:54

remember I looked over and there

31:56

she was and I walked over and we

31:58

hugged and I said Are

32:00

you nuts? What are you doing here? You're going

32:02

to get in trouble with your parole. And she

32:04

said, I don't care. Of course I'm

32:06

here. I'm

32:10

so sorry. I'm

32:13

so sorry. I'm

32:16

so sorry. I stepped up

32:18

and organized this demonstration to pressure

32:20

the Federal Public Health System to

32:22

recognize women with HIV. Their

32:25

focus was the fate to change the

32:27

definition of AIDS. Change

32:29

the definition. Now to

32:31

understand this fate, it's important to remember

32:34

the basic difference between HIV and AIDS.

32:38

HIV, or human immunodeficiency

32:40

virus, is, well, a

32:42

virus. It disables your immune

32:44

system. And when it gets really

32:46

advanced, it can lead to a bunch

32:49

of illnesses that are collectively known as AIDS, or

32:52

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

32:55

Now, when Centers for Disease Control first

32:57

came up with its list of AIDS

32:59

defining illnesses, it based that

33:01

list on what they were seeing in men.

33:05

And it excluded illnesses that were showing

33:07

up in women, like... Yeast infections,

33:09

one after the other. Pelvic inflammatory

33:12

disease. Cervical cancer. And

33:14

this led to a lot of problems. First, it

33:16

meant that a lot of women with these symptoms,

33:18

they didn't know that they had AIDS, or that

33:20

they might have AIDS. But

33:23

it also meant that even when a woman knew

33:25

she was HIV positive, and when she was really,

33:27

really sick, she still couldn't

33:29

get an AIDS diagnosis. And

33:31

this meant that she couldn't qualify

33:33

for government benefits, like Medicaid and

33:36

disability. And Katrina was one

33:38

of them. So she joined the campaign, By Act

33:40

Up, to get the CDC to change the definition

33:42

of AIDS. So I've watched,

33:44

and as an HIV-positive woman, I

33:47

too have something, somebody's symptoms. It's

33:49

important for you to know that

33:53

women are ill prior to any diagnosis

33:55

of HIV, and that

33:57

they often die of HIV complications.

34:03

It's just a few weeks after the march

34:05

in D.C. now and Katrina is down in

34:07

Atlanta speaking to a bunch of bigwigs at

34:09

the CDC. She's there with

34:11

Maxine Wolf. Now Maxine, she

34:13

is not a doctor and she's not a

34:16

health professional. She is

34:18

an activist. I had to give a

34:20

whole list of the

34:22

assumptions that were underlying the

34:24

fact that women were not being treated.

34:27

Did you feel like you accomplished stuff and you actually managed

34:29

to move them in that meeting? No, we

34:31

didn't feel like we moved them. We felt like we

34:34

told them what they needed to know. When

34:37

we were walking out Katrina just turned around and looked

34:39

at them and she said, I hold

34:41

you responsible for

34:44

every woman with HIV who

34:46

dies, including myself. And

34:49

we left. They didn't say anything. They

34:51

were just standing there with their mouths open. I

35:00

can remember, in fact, I'm having a visual film

35:03

going in in my mind right now of

35:05

when I had a number

35:08

of women activists come into my conference

35:10

room on the seventh floor

35:12

of building 31 on the NIH

35:14

campus decades ago. That's

35:17

Dr. Anthony Fauci. He was the

35:19

director of the National Institute of Allergy and

35:21

Infectious Disease and that meant that he ran

35:23

AIDS research in the United States. It

35:26

also made him a target for criticism from

35:28

activists like the ACT UP people who were

35:30

in this meeting who were really, really frustrated

35:33

with how many people were dying and how

35:35

little the government seemed to be doing about it.

35:38

Do you happen to remember just one woman

35:40

who was part of that, Maxine Wolf? Oh,

35:43

yeah. She was a tigress. I

35:47

mean, she was very proactive, maybe even

35:49

a little aggressive. But, you know, when

35:51

people are not listening to you retrospectively,

35:53

you end up respecting them for being

35:55

that way. Yeah. I

35:57

mean, we've talked to a number of women who... said

36:00

that, you know, in the late 80s,

36:02

they really had to work to

36:04

convince their doctors to test them

36:07

because this idea that women could get

36:10

HIV just wasn't out there in

36:12

the general public that much. I

36:15

think, yeah, I think you somehow

36:17

or other the message was

36:20

either not getting to or the

36:22

general very, very busy private

36:25

physician who was in a region

36:27

of the country or who has

36:30

a population of patients

36:33

that you would not intuitively

36:35

feel would be at risk.

36:39

Where do you think the bridge fell apart?

36:41

You know, what was missing in the translation?

36:44

You know, if I had a clear-cut answer, Lizzie,

36:47

I would tell you, I don't know. It's as

36:49

puzzling to me. I

36:51

think there are multiple complicated

36:54

reasons why that happens.

36:56

The lack of people connecting the

36:59

dots. I've been saying it now

37:02

for 42 years that

37:05

everybody can be at risk. Fauci

37:10

wasn't exaggerating. He actually did write

37:12

an article that was published years earlier,

37:14

and it's said that everybody expected the disease

37:16

to go beyond gay men. Even

37:22

so, women were still being excluded

37:24

from treatments and studies. In

37:26

the medical establishment, it was never, it

37:28

wasn't moving. And

37:30

then in December 1990, activists

37:33

scored a breakthrough. There was

37:35

a conference. Finally, because of all

37:37

this pushing, there was a conference at

37:40

NIH about HIV and women. Dr.

37:42

Kathy Anastas was there. She

37:45

became an AIDS expert through her work at

37:47

Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. It's

37:50

almost 10 years into the epidemic, and

37:52

this is the first national conference that

37:54

focuses on women. A lot

37:56

of people invited who had been pushing

37:58

to have more studies available. HIV and

38:00

women, have any study of HIV and women

38:02

actually. Activists, doctors,

38:05

researchers, they were all there and

38:07

they were fired up. They were

38:09

not going to leave without getting something. During

38:12

that meeting is

38:15

when Tony Fauci

38:18

decided that they needed a study

38:20

of women. Finally,

38:22

a study about women. It

38:25

didn't begin until 1993, but it continues to this day. And

38:29

it is the largest study on

38:31

the progression of HIV in women in

38:33

this country. But

38:41

studies take a long time, especially

38:44

when you have an incurable disease. Katrina

38:48

had tested positive for HIV three

38:50

years earlier and her immune system

38:52

was getting weaker. She

38:54

was getting sicker. She didn't

38:57

have a lot of time and there was

38:59

a lot that still needed to change. So

39:02

she kept speaking out. Katrina

39:24

has had an act up protest outside the

39:27

Department of Corrections in Albany, New York.

39:37

She's wearing this fake prisoner costume and

39:39

she's got this black leather hat, tilted

39:41

kind of to the side, a nose

39:43

stud, gold hoop earrings. And

39:46

because I want adequate health care for prisoners

39:48

that I left there and it shouldn't be

39:50

a death sentence that they have HIV, I

39:52

want education for them, peer education. I want

39:54

them to let out terminally ill individuals due

39:57

to HIV because that's like

39:59

double. and it becomes a death sentence

40:01

for those individuals. And if they

40:03

pose no threat to society, let them out

40:05

and let them die in dignity. So that's

40:08

why I'm here. I'm the

40:27

I feel like she changed the definition of AIDS.

40:29

And she did this on the one hand with

40:31

ACT UP through its campaign against the CDC.

40:34

But she also worked with Terry McGovern on

40:36

her lawsuit, the one against the government. So

40:39

I feel like she taught me this

40:41

concept of joyful resistance. It's

40:47

joyful that we

40:49

get to fight this together. It's

40:52

joyful that we're standing up and

40:54

resisting. Yes, we are

40:56

being victimized, but we are not

40:58

victims. We're models of

41:01

resistance. But

41:07

Katrina was more than a model of

41:09

resistance. She was also an advisor.

41:13

As the lawsuit was winding its way through the

41:15

courts, Terry would go to her for guidance. She

41:18

was my primary strategy

41:20

advisor. I think she

41:22

really loved the other women that she saw

41:24

being mistreated and saw

41:26

dying. She really was

41:28

drawn to the law and justice because

41:32

some part of her just couldn't ever be

41:34

okay with this. Katrina

41:37

was not well for very

41:40

long on the outside. Like she

41:42

kept getting pneumonia and lots of

41:44

gynecological problems and couldn't qualify for

41:46

Medicaid or disability. Even

41:49

Katrina couldn't get an AIDS diagnosis, only

41:52

HIV. That meant

41:54

as she got weaker, she didn't have a home

41:56

care attendant. Here was, in my

41:58

view, one of

42:00

the biggest heroes, I hate that word, but really.

42:03

She was falling on the floor with nobody

42:05

to pick her up. We were sending clients,

42:09

patients, volunteers to go help

42:11

her. Katrina

42:14

was in and out of the hospital. She

42:16

was at St. Luke's Roosevelt a lot, and

42:18

she'd have high boots on

42:20

and in the bed. I'd be like, why are

42:22

you wearing these high boots? You said I snuck

42:25

out and went shopping. Then every time

42:27

I went to see her, she used to steal my wallet.

42:32

She'd say missing anything, she did it a

42:34

few times. So she was

42:36

so lively, actually, and funny, and

42:38

so wanted to live. Finally,

42:45

after years of fighting in the fall of 1992,

42:49

the CDC offered the activists a

42:51

deal. They were gonna change

42:53

the definition of AIDS, but it

42:55

wouldn't include every symptom the activists had asked

42:58

for. And they

43:00

were offering this compromise of

43:02

bacteria pneumonia, tuberculosis, cervical

43:04

cancer, and 200 or furious T

43:06

cells. I remember

43:08

having very serious conversations with

43:10

her. Katrina, from her hospital

43:13

bed. And she

43:15

felt strongly that we should take it, that

43:18

it was too important to not

43:20

take it at this point, especially

43:23

with the 200 T cells, that that

43:25

would bring a lot of people in. And

43:29

yes, there should be many more things

43:31

in it, but there's no

43:33

time for this, as I remember her saying.

43:36

In October 1992, Terry and the

43:39

coalition of activists decided to accept

43:41

the CDC's offer. Terry

43:43

raced to the hospital to tell Katrina.

43:46

Because I wanted Katrina to make a

43:48

statement. So I told her that the

43:50

definition was being expanded, and then she

43:53

gave this statement that

43:55

was kind of saying, you know,

43:58

this never would have happened. been

44:00

without women standing up for themselves, without

44:02

activists. This is not the way this

44:04

should be, right? And

44:07

I couldn't say she was happy. She

44:09

was dying. She was so angry

44:11

and wanted the record to

44:14

reflect that we had to

44:16

fight tooth and nail to be acknowledged

44:18

of dying of AIDS. The

44:28

new CDC definition was set to go

44:30

into effect in January 1993. So

44:34

if Katrina lived into the new year,

44:37

she would get the AIDS diagnosis. But

44:41

she didn't live. Katrina

44:44

Haslip died on December 2, 1992.

44:49

She was 33 years old. For

44:57

Katrina to die and never get AIDS, given

45:00

who she'd been, I

45:03

started to just feel just like

45:06

she was shocked in a second. After

45:11

three years of fighting, Terry and the activists

45:13

had won. But Katrina

45:15

had died. And it

45:18

was too late for scores of other women with AIDS.

45:21

I really have this recurrent memory of

45:24

walking into the office here, and

45:26

it was those pink messages, like

45:29

piles of messages of clients that had

45:31

died. It kind of felt

45:33

like everybody was dying. And the plaintiffs in the

45:35

lawsuit were dying. So we were winning.

45:37

Who cares, right? But

45:44

the victory did matter. The number of women

45:46

diagnosed with AIDS went up 45% after

45:50

the CDC changed its definition. And

45:53

that's because all of a sudden, HIV-positive

45:55

women suffering from one of the newly

45:57

included symptoms, they were being killed. being

46:00

counted as having AIDS. It's

46:04

ultimately really weird to win

46:07

lawsuits for people who are dead. Even

46:10

when I teach it, like I teach at a school

46:12

of public health. So I try to say,

46:15

here's why science is not neutral. Right. And

46:17

I, whenever I show that 45% increase slide,

46:19

I never feel joy. I

46:24

feel really angry and sad. Most

46:29

of these women are not around to

46:31

be in the films. On

46:33

the other hand, as I have, I hope

46:36

been able to describe, I carry them. Right.

46:39

But nothing about this is okay.

46:49

Did you have a memorial for her in

46:51

the prison? Yes. We did. And

46:54

I think we also had the quilt for

46:58

Katrina. A wilde Gonzales.

47:01

She was still in prison when Katrina died.

47:03

She was released a few years later. And

47:06

she and a group of women, they stitched

47:08

a panel for the AIDS Memorial quilt

47:10

in memory of Katrina. Because, you

47:12

know, the quilt was also part

47:15

of our therapy. Every

47:17

time somebody passed away. So

47:19

we will get together and design the

47:22

quilt and we will sit around that

47:24

big table to design it and to talk

47:26

about the person and to share

47:28

beautiful memories. And yeah,

47:32

that was part

47:34

of our therapy. Katrina was

47:36

a powerful, determined woman.

47:40

She fought to the end. That's

47:43

what counts. She

47:49

got the chance to be a movement

47:52

leader, an eloquent, powerful,

47:55

incredibly impactful movement leader.

47:58

That's Judith Clark again. She was

48:00

released from Bedford in 2019. But

48:03

she didn't get the chance to

48:05

then say, OK, that's

48:07

great, but what about my life and

48:09

who I want to be? Which

48:13

is a challenge that all of us have

48:16

as we enter

48:19

life outside of prison. Before

48:23

she died, Katrina wrote the introduction to

48:25

an oral history of Ace called Breaking

48:27

the Walls of Silence. And

48:29

it's the story of how these women

48:32

came together and began changing the story

48:34

of AIDS for women. Ah,

48:36

Katrina, Katrina de Medida. Page

48:40

10. OK. Let

48:43

me see. Katrina's old friends,

48:45

Wendy and Judy, they're going to read her words.

48:49

We were the community that

48:51

no one thought would help itself.

48:55

Social outcasts because

48:58

of our crimes against society

49:01

in spite of what society

49:03

inflicted upon some of us. We

49:06

emerged from the nothingness with a

49:08

need to build consciousness and to

49:10

save lives. We made

49:12

a difference in our community behind the

49:15

wall. And that difference has allowed me

49:17

to survive and thrive as a person

49:19

with AIDS. To

49:22

my peers in Bedford Hills Correctional

49:25

Facility, you have truly

49:28

made a difference. I

49:30

can now go anywhere and stand

49:33

openly alone without the

49:35

silence. Katrina

49:37

Haslip, 1990. Today,

49:51

the medical establishment in the

49:53

United States fully recognizes that

49:55

women can get HIV and

49:57

AIDS. The field of women's health is more

49:59

than a year. much more robust. And

50:02

women with HIV are surviving and

50:04

yes, thriving into their 50s, 60s,

50:06

even 70s. But

50:10

we have so much farther to

50:12

go. To

50:18

hear other stories from the early days

50:20

of the HIV and AIDS epidemic like

50:22

the hospital ward that became a makeshift

50:25

home for kids with AIDS and

50:27

a woman who set up a DIY needle

50:29

exchange program in her South Bronx neighborhood, subscribe

50:32

to the podcast series Blindspot, The

50:35

Plague in the Shadows from the

50:37

History Channel and WNYC studios. Our

50:40

episode was produced by Michael I.

50:43

Schiller and edited by Taki Telenides.

50:45

The Blindspot team includes Emily Botin,

50:47

Karen Schrowman, Anna Gonzalez,

50:49

Sophie Hurwitz, and Christian Reedy.

50:52

Music and sound design for the podcast

50:55

by Jared Paul. Additional music by Isaac

50:57

Jones and additional engineering by Mike Kutchman.

51:00

The executive producers at the History Channel

51:02

are Jesse Katz, Eli Lehrer, and Mike

51:04

Stiller. Victoria Baranetsky is

51:07

our general counsel. Our production managers

51:09

are Stephen Raskone and Zulema Cobb.

51:11

Additional score and sound design for

51:13

this episode by Jay Breese, Mr.

51:15

Jim Briggs, and Fernando Mamayo Arruda.

51:18

Our CEO is Robert Rosenthal. Our

51:20

COO is Maria Feldman. Our interim

51:22

executive producers are Brett Myers and

51:24

Taki Telenides. Our theme music is

51:26

by Comorado Lightning. Support for Reveal

51:28

is provided by the Revan David

51:30

Logan Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the

51:32

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

51:34

Foundation, the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation,

51:36

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the

51:39

Park Foundation, and the Hellman Foundation.

51:41

Reveal is a co-production of the

51:43

Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX.

51:46

I'm Al Ledson, and remember, there's always

51:48

more to the story. From

52:02

BRX.

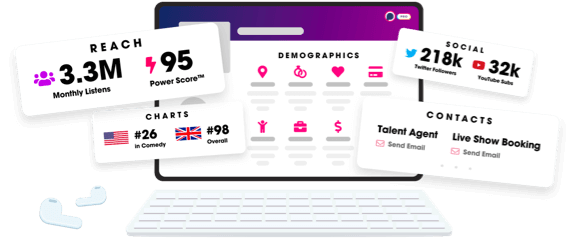

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us