Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

Canadians care about what's happening in the

0:02

world and in just 10 minutes World

0:04

Report can help you stay on top

0:06

of it all. Join me, Marcia Young.

0:09

And me, John Northcott, to get caught up on

0:11

what was breaking when you went to bed and

0:13

the stories that still matter in the morning. Our

0:16

CBC News reporters will tell you about

0:18

the people trying to make change. The

0:21

political movements catching fire. And

0:23

the cultural moments going viral. Find

0:26

World Report wherever you get your

0:28

podcasts. Start your day with us. Welcome

0:59

to the final keynote and final

1:01

session of the Summit. Welcome

1:05

to the final keynote and final session of

1:07

the Summit. It

1:30

is my tremendous pleasure to introduce

1:32

our final speaker, Jesse Wente. The

1:35

closing address at the Forum was given

1:37

by the current chair of the Canada

1:39

Council for the Arts, a

1:41

writer and broadcaster who was the

1:44

founding director of the Indigenous Screen

1:46

Office. My name is

1:48

Jesse Wente. I'm a father and

1:50

a husband who lives in Toronto.

1:53

And I'm Anishinaabe Ojibwe. My

1:55

family comes from Chicago on

1:57

my dad's side and Ganaba-Jing

1:59

Anishinaabe. on

2:02

my mom's side, and I am Bear Clan.

2:05

Jesse Wente's aspirational future

2:07

envisioned different forms of

2:09

nationhood from what currently

2:11

exists, and better ways

2:13

of being for all people informed

2:15

by the best parts of the

2:18

indigenous past. Here

2:20

is Jesse Wente's talk at Imagining

2:22

2080. It's

2:25

called Remembering Our

2:27

Future. I'm

2:30

often asked to speak the ideas of truth and

2:37

reconciliation, social justice, and

2:39

indigenous sovereignty, but lately,

2:41

like at this gathering, I've been asked

2:43

to think about and speak to the

2:45

future. These requests I

2:47

find very fascinating. I'm

2:50

not really a futurist, or

2:52

at least I wouldn't really classify myself as one,

2:55

but I do really think a lot about the

2:57

future, and I'm always trying to act with the

2:59

future in mind that is the Anishinaabe way. We

3:02

believe that everything you do you should

3:04

consider. It impacts seven generations into the

3:07

future, so as you can

3:09

imagine, that requires a lot of thinking about what

3:11

we do and how it's gonna impact people in the future.

3:15

It also strikes me that perhaps this

3:17

request is because for indigenous

3:19

people, especially when I think

3:21

about requests to think about the future in this

3:24

moment with what's going on in the world,

3:27

it strikes me that perhaps we're being asked because

3:30

we do as a community have some

3:32

experience in both long-term planning and

3:35

apocalypse preparedness and survival.

3:38

We are, after all, post-apocalyptic.

3:42

Our world ended, and

3:45

we survived, and we're still here. And

3:48

now we are all here, and perhaps it's

3:50

the time that we begin to lend this

3:52

particular expertise in surviving the end of

3:54

the world to this one.

3:57

That would certainly align with one

3:59

of our Anishinaabe. bay prophecies around

4:01

what we should be doing and why this where

4:03

we might even be having these sorts of discussions

4:06

in this moment. And I say

4:08

this not to be depressing, surprisingly, but

4:11

rather hopeful, as we are proof

4:13

that cultures can endure the most systemic of

4:15

ongoing attacks, and not just

4:17

survive, but begin to thrive again. We

4:20

are evidence that cultures can withstand global

4:22

systems change, adapt and

4:24

rebuild. We are

4:27

evidence of the power of memory and remembering,

4:29

as that is both what preserved us and

4:32

now what we must preserve. Even

4:36

as our ancestors watched their world end,

4:38

they prepared for the future. They

4:41

imagined what it would be, and

4:43

then they did things to

4:45

ensure that what they imagined could

4:47

be realized. So I want

4:49

to tell you a story. It's a

4:52

personal story. It's about my family, my community,

4:54

my people, my nation, but I

4:56

think it has some relevance to today. So

4:59

my great grandparents on my mom's side were

5:01

named Alex and Maggie Miowas to

5:21

Ganabajing so that they could meet

5:24

me. They had had a dream

5:26

of my birth. They dreamt of

5:29

a young boy, a baby, being blown down

5:31

the Serpent River into the community by the

5:33

wind. So

5:35

they asked to meet me, and there they gave

5:38

me the name, Noden, which

5:40

is on my birth certificate. And

5:43

it means wind in our language

5:45

to signify the wind that blew me

5:47

into the community. I'm

5:50

the only one of their great grandchildren to have

5:52

a name like this. In

5:54

fact, I'm the only one of their family to

5:57

have a name like this. Their children, they did not.

6:00

a name like this on them. Alex

6:04

and Maggie spent most of their lives where they had

6:06

always been. Maggie was the

6:08

midwife and medicine woman for the community and

6:11

Alex served as chief for a time

6:13

but was also mostly a trapper, mostly

6:16

beaver and minx. They

6:19

had a small farm. They lived

6:21

off the land pretty much exactly

6:23

as their ancestors had done for,

6:26

well as my grandmother would put it, ever, forever.

6:30

Although now they sold their furs to the Hudson's

6:32

Bay Company as opposed to trading them with other

6:34

nations. Alex

6:37

and Maggie had eight children, my

6:39

grandmother Norma, among them. Now

6:43

it's important to

6:45

keep in mind that Alex and Maggie,

6:48

despite being very traditional people, were

6:51

also keenly aware that their way of

6:53

life was ending and

6:56

that their children would not live in

6:58

the same way that they had and

7:00

their parents had and the entire line

7:02

of their family had lived. They

7:05

were already living on a reserve, something

7:07

that was unimaginable to their own parents.

7:10

They were beginning to see their traditional

7:12

territory taken away, the hunting grounds which

7:14

extended well beyond the reserve lands, and

7:17

this is even before, this is actually

7:19

long before, the uranium mines would poison

7:21

the river for two generations. So

7:24

what did they do? Knowing

7:27

that such seismic change was coming,

7:29

and I have to say I

7:31

think a lot about what our

7:33

folks did when

7:35

they knew, because you have to understand

7:38

First Nations people really did know that

7:40

our world was ending. We

7:42

understood. So what did we do?

7:46

First, they sent their

7:48

kids to the school the church wanted them to. They

7:52

wanted their kids to learn English because they

7:54

understood even though they did not speak English,

7:57

that the world was going to speak English.

7:59

and that their kids must know this language.

8:03

So they wanted their kids to learn

8:05

the skills needed to thrive in this new world,

8:08

but not all the kids. And

8:10

this is important, OK? Five

8:14

of the eight children went

8:16

to the schools. There were two schools

8:18

in Spanish, Ontario, St. Peter Claver School

8:21

for Boys, and St. Joseph School

8:23

for Girls. You can look them up in the

8:25

National Center for Truth and Reconciliation

8:27

if you want to know the history. That's not

8:29

really what this talk is about, but just know

8:31

that bad shit absolutely happened there. Five

8:36

of the eight kids went to the schools. The

8:38

youngest did not. That

8:40

was both because Alex and Maggie realized that

8:42

the schools were not the promise that they

8:44

had held themselves out to be, but

8:47

also because those kids

8:49

were to learn something else.

8:53

So some of the kids didn't go

8:55

to the schools. Alex

8:57

and Maggie made sure they kept their

9:00

language. They, in fact, moved

9:02

the family off the reserve just across the

9:04

street, but it was enough of a move

9:06

that meant that the Indian agents and the

9:08

RCMP didn't come to collect the kids

9:10

at the school year. These

9:12

kids would keep the

9:14

language. These kids

9:16

would keep the ways, the

9:19

stories, the ceremonies, the knowledge.

9:22

Yes, some were sent to learn the

9:24

new ways in order to bring

9:26

that knowledge back to the community. Others

9:29

were kept so

9:32

that they would learn the traditional ways to

9:34

keep them and protect them in this new

9:37

world for when we would want them again.

9:40

Ours was not the only family that

9:43

did this. Ours was not

9:45

the only community that did

9:47

this. In many ways,

9:49

a lot of our communities did

9:51

this exact same thing. There

9:53

was a painting at the Canada Council offices

9:55

at a gallery there by an indigenous artist,

9:58

and it's called The Kids. The kids that didn't

10:00

go, the kids that were left behind, or

10:03

kept behind. And it's this

10:05

really evocative image of a Indian

10:07

reservation with a single kid sitting on top of

10:09

the hood of a car. This

10:11

is the exact story I'm telling to you.

10:15

This is why we

10:17

still have our songs. This

10:19

is why we still have our dances,

10:21

our stories, even our languages, so

10:24

attacked for generations, but they

10:26

persist and indeed are making

10:28

comebacks all across Turtle

10:31

Island. When

10:33

my great grandparents and those like them made

10:35

these plans, made these decisions,

10:37

and took these actions, it was

10:39

with the knowledge that they would

10:41

not live to see their future

10:43

realized. Right? Although I

10:46

have to say I can see the evidence of their work

10:48

now, all around in

10:50

the family. So there's a part of my family,

10:53

the family of the kids that didn't go to

10:55

the schools. Those are the

10:57

folks in my family that still live in the community. They

11:00

still speak Anishinaabe Mowin. My cousin Steve,

11:02

who's of my grandmother's generation, he's my

11:04

cousin, but he's I think 28 years

11:06

older than me. But

11:09

he's of my grandmother's generation. He is

11:11

a language holder. He

11:13

teaches the language in the community. He

11:15

teaches the kids how to live a

11:17

traditional life. And

11:20

there's a whole branch of my family, of the

11:22

Miwaskis, who are still in Serpent River, living

11:24

as close as they can to the

11:26

old ways in this world. Then

11:30

there's the other part of the family, of which

11:32

I am a part, the

11:35

part of the family that did go to the schools, whose

11:37

ancestors did go there to learn these new

11:40

ways. And that part of the family

11:42

did not go back to the reserve, which was of

11:44

course the intended outcome for the schools. But

11:46

I have to say, was

11:49

also somewhat the intended outcome of my

11:51

great grandparents. They wanted these

11:53

children to go out into the world to

11:56

learn things in order to bring them back,

11:58

in order to strengthen the community's abilities. to

12:00

survive in this new world. So

12:04

those kids went out and

12:06

that side of the family, well one of them is standing

12:09

in front of you, who does

12:11

this work? My sister, she's

12:13

a partner in an indigenous law firm and she

12:15

sues the government every day. That's

12:17

what she does and she wins. Every

12:21

day she wins. The

12:24

rest of my family is likewise engaged. My aunt,

12:27

she started the indigenous arts program at OCAD,

12:30

Bonnie Devine. Another

12:32

aunt is in risk management for

12:35

a large not-for-profit organization that

12:37

serves our communities. We've

12:39

all done, fulfilled,

12:41

exactly what my

12:44

great-grandparents were imagining. We

12:46

all left the community and it meant a huge

12:48

sacrifice and I can't say it's not without pain, right,

12:50

because I miss my language even though I don't

12:52

know it. I miss so much of these things but

12:55

it has meant that I

12:57

have fulfilled exactly what they wanted. I've

12:59

learned a whole bunch. I've learned this

13:01

new language, frankly, better than

13:03

most people who are born into it, right.

13:07

I've learned all of these skills in order

13:09

to help my community.

13:13

This is not a story that is

13:15

my family's alone. It is a common

13:17

story, a common relationship for so many

13:19

people, families, and communities. If

13:21

you ever wondered why indigenous people

13:23

can still round dance, this is

13:25

why. We understood

13:29

that our world was ending and

13:31

we made plans for what to do after.

13:33

It was always understood

13:35

that we would still be here, the people

13:37

would still be here, even if our way

13:40

of life was not. So how

13:42

do we exist, persist

13:45

in those conditions? And

13:47

I don't think that it is so foreign for

13:49

us now to think that we can also begin

13:52

to make plans, plans

13:54

that will come to fruition long

13:56

after we are gone. Certainly

13:58

that's how I've... imagined my

14:01

existence. So for example, I

14:03

started something called the Indigenous Screen Office in 2018.

14:06

I was the founding director. The

14:09

Indigenous Screen Office is a funding

14:12

body for storytelling on screen for Indigenous

14:14

people. It had been the dream of

14:16

our community to have this since

14:18

the early 1990s, because Australia got an

14:20

Indigenous Screen Office in like 1993, and

14:23

the day after a bunch of us started advocating for

14:25

one here. So

14:27

it took 25 years of advocacy

14:31

to get this screen office in. And we

14:33

established it in 2018

14:36

at the time that I started it, just to give

14:38

you some idea. Like so many things

14:40

in Indian Country, it was funded to fail.

14:43

So my first budget was $235,000 annually. There

14:47

was one staff, me as the founding director.

14:49

That was it. When I

14:52

left my job there, which was always

14:54

the plan, the budget was $17 million

14:56

in four years. So

14:59

that's what they're currently doing. Now,

15:02

when I was talking about this, and

15:05

especially when I was talking to the

15:07

government about like why we wanted this,

15:09

and what was the point of this,

15:13

I definitely told them a story about what the

15:15

point was. It's not the real story, but I'll

15:17

tell you the story I told them, which

15:20

was the story was around us

15:22

participating in this large economy that

15:24

we've been largely locked out of

15:26

in Canada. It was about us

15:28

telling stories that we think are

15:30

much needed. It was about us being

15:33

a sovereign people, having equal quality with French

15:35

and English. So why they have funding for

15:38

movie and TV projects, why shouldn't we have

15:40

funding for movie and TV projects? The history

15:42

of it is that our stories are told

15:44

by other people on this land, and that

15:46

if you have gathered, hasn't really benefited us

15:49

that much. These were all the arguments that

15:52

I talked about. Economic participation, all of this

15:54

stuff. And I

15:56

believe in all of those things. Those are

15:58

all really valuable things. not at

16:00

all why I started the Indigenous Screen Office. That

16:03

is not the goal of it. And

16:05

if you ask Carrie Swanson, who runs it now, she'll

16:07

list everything I just said. And

16:10

then if you catch her, especially if she's with

16:12

Indigenous people only, then she'll tell you the real

16:14

reason of what we're doing, which

16:17

is sovereignty. That's it, full

16:20

stop. Now, the name I gave it at the

16:22

time was narrative sovereignty, because that's a little less

16:24

threatening to the state. If

16:27

they just think it's about stories. But

16:29

of course, the state, the

16:32

Canadian state, in most states, colonial

16:34

states like the one we exist in, and

16:36

these colonial systems, one of

16:38

the advantages we have as people, okay,

16:41

especially for those of us who are still

16:43

connected with sort of a different understanding

16:46

of the world, is

16:48

that these places run on quarterly

16:52

reports and annual reports, right? But

16:55

that's not actually how we work. If

16:58

we wanted to write a report, it would be

17:00

called a generational report, because

17:02

I believe we work in generations. That's

17:05

how I work. So the whole

17:07

idea of like, well, I'll sell narrative sovereignty now,

17:10

because I can sell that now, it'll be bought.

17:13

They'll fund this thing, which they have. They

17:16

don't need to know the longer goal. They're not gonna

17:18

be alive to see it anyway. But

17:21

I need to know what we're doing, and the

17:24

people that work there in our community needs to know what

17:26

we're doing. And the whole point is, if

17:29

over time, indigenous people tell our

17:31

own story, then

17:34

non-indigenous people will begin to realize that

17:37

we are still sovereign, and that is what is owed

17:39

to us. And that over time,

17:41

it will bend, because

17:44

storytelling is how Canada exists, right?

17:48

And occupation. But

17:50

that's how it exists. It tells the story of its

17:52

existence. We can tell

17:54

a different story and come up with a different

17:57

sort of existence. And

17:59

the reason I... I named a talk,

18:01

Remembering Our Future, is

18:05

because for Anishinaabe, we have a very different

18:07

understanding of time and how time

18:09

works. And so what

18:11

I would say is where we are now in

18:13

the world with everything that is going on, we

18:15

have already been here. If you're

18:18

worried about what's happening in Israel and

18:20

Palestine, it's important to understand that that

18:22

happened here. That happened

18:24

here. We're just a

18:26

few hundred years after it happened. So

18:29

the present we're in is just

18:31

something we've actually already experienced, which

18:34

is to mean we shouldn't despair because

18:36

the fact that we are here is

18:38

evidence that we survived that calamity. It

18:41

also means that the future

18:43

has already also existed, if

18:46

you understand what I mean. The

18:48

future that you're imagining has already happened,

18:51

has already existed. What we need to

18:53

do is remember that future,

18:56

remember what it was to

18:58

exist before these systems that are

19:00

harming us so much. Particularly

19:03

in places of settler colonialism,

19:05

which is much of the world, we

19:07

need a deep remembering. A

19:10

remembering so deep that most people can't

19:12

even, don't even understand what I'm saying.

19:14

But I'm talking blood level

19:17

memory, where you have to really

19:19

think well beyond your life,

19:23

your parents' life, your grandparents' life.

19:26

We need the deepest of human

19:28

memories in this moment. And

19:30

that memory will allow us to remember

19:32

the future we're all thinking about right

19:34

now. The systems we have

19:36

here on this place now that are hurting

19:39

us, that are causing us to war, causing

19:41

us to divide, causing all of this harm,

19:44

they didn't always exist here. They

19:47

didn't always exist, period. They're

19:51

actually very new. And

19:53

so for some communities, like

19:55

say for First Nations people,

19:58

this deeper remembering actually fairly

20:00

easy because we

20:02

were, it's not so long ago for us

20:05

to remember when none of this was like this. I

20:09

can remember, even though I didn't live it, I

20:11

can remember. I remember in the songs and in

20:13

the dances and the stories, all

20:15

that stuff that my great-grandparents

20:18

made sure our community preserved is

20:20

now the way we remember how

20:22

to get back to where they were. Do you

20:25

understand? It's a path. They

20:27

led us a path to the past

20:30

so that we may build the future. The

20:33

solutions to the systemic issues we face lie

20:36

beyond the systems that created them. This

20:39

is also why we must remember deeply. We

20:42

will not resolve the issues of

20:44

capitalism through a new marketplace. That

20:47

is not what will happen. What we

20:49

have to do is deeply remember what

20:52

it was to exist without capitalism. What

20:55

we have to remember, is deeply remember, is

20:57

what it was to exist without patriarchy. Not

21:01

that hard for Anishinaabe, we are

21:03

matrilineal culture. It was

21:06

not that long ago that the women

21:09

were the decision-makers in our communities. We

21:11

can remember this very much. Here's

21:14

the trick. All of you can remember

21:16

the same things because these are all memories that you

21:18

also have deep

21:21

inside. These

21:23

systems did not spring up when

21:26

creation happened. It

21:28

took eons of time

21:31

for us to develop these systems. Whole civilizations

21:33

have come and gone. It's deeper

21:35

remembering. It's there. You

21:37

can't solve the issues of colonization by

21:40

colonizing others. We

21:43

actually have to end the whole notion of

21:45

colonization. We won't escape capitalism through markets,

21:47

as I said. We must remember what

21:49

it was to exist beyond these things

21:51

in order to escape them now. This

21:54

is another reason why I've invested so

21:56

much time in storytelling, and particular storytelling

21:58

from people who are not part of

22:00

the mainstream, other voices.

22:03

Because it's when the storytelling can

22:05

happen, when we can hear another

22:07

person's vision of the future, that we can actually

22:10

begin to wait a minute, that works. I'll tell

22:12

you a quick, and it seems

22:14

so trite, but I'll give you an example. Years ago, I

22:16

did an exhibition around Star Trek, thrilled.

22:20

As a lifelong trekker, I was just so

22:23

over the moon. We were

22:25

putting together this exhibition

22:28

on Star Trek.

22:32

One of the things that struck me about it is

22:34

that one of the writers,

22:36

the first time we as

22:39

a human species saw

22:41

an iPad or a cell phone was

22:43

on Star Trek in 1967.

22:45

It was actually a

22:47

woman writer who wrote that particular episode.

22:50

We all watched as this person pulled

22:53

out this thing and did all

22:55

this stuff and scanning human bodies and doing

22:57

all this fancy stuff, none of which existed

22:59

at the time. They were

23:01

painting us a vision of the future. But

23:04

the reason why that story was so important

23:06

is because I don't believe we ever actually

23:08

get to this if we

23:10

don't have that vision. The

23:13

reason it's sharing is the writer, she did

23:15

not know how to make this. She

23:18

knew how to write a great piece of

23:20

television, so she did that. But someone watching

23:22

that show, someone who heard that

23:24

story, well, they did know how to make

23:26

this. So

23:28

they made it. One

23:30

of the reasons storytelling is so important, one of

23:33

the reasons why we need to hear stories not

23:35

just from the people who've been telling

23:37

stories for a long time, but from the people

23:39

who have not been telling their stories, is that

23:42

that allows us to imagine a very different

23:44

future than the one we're in. That allows

23:46

us to imagine something we couldn't even conjure

23:48

at the time. And when

23:50

we share it, it means someone else who does

23:52

know how to do the thing will

23:54

do the thing. Right?

23:57

It doesn't have to be us. We don't have, just

23:59

because I dreamt up the

24:02

iPad like they did on Star Trek,

24:04

does not have to be them who creates it and makes

24:06

it a reality. So the importance

24:08

of storytelling and storytelling that exists and

24:10

comes from a place that is beyond

24:12

this time now, that

24:15

engages with that deeper memory, that

24:18

has a knowledge of systems beyond this,

24:20

that's the stories we need right now

24:22

so that we can begin to imagine

24:24

and remember what it was to

24:27

live in a different way. Remember what it was

24:29

to live as a

24:31

community altogether, not separated into

24:34

separate communities or different identities,

24:36

but altogether, what it

24:38

meant, the obligations that we would have

24:40

to one another, right? All

24:43

of these things, we need to remember all

24:46

of them. You're

24:59

listening to a public talk

25:02

by Jesse Wente, writer, broadcaster

25:04

and arts administrator here on

25:06

Ideas. We're a

25:08

podcast and a broadcast heard on

25:11

CBC Radio One in Canada, on

25:13

US Public Radio, across

25:15

North America, on SiriusXM,

25:17

in Australia, on ABC

25:19

Radio National, and

25:22

around the world at

25:24

cbc.ca/ideas. Find us

25:26

wherever you get your podcasts. I'm

25:29

Nala Iyad. Canadians

25:32

care about what's happening in the world and

25:34

in just 10 minutes, World Report can help

25:37

you stay on top of it all. Join

25:39

me, Marcia Young. And me, John Northcott, to

25:41

get caught up on what was breaking when

25:43

you went to bed and the stories that

25:46

still matter in the morning. Our

25:48

CBC News reporters will tell you about

25:50

the people trying to make change. The

25:53

political movements catching fire. And

25:55

the cultural moments going viral.

25:57

Find World Report wherever you

25:59

get. your podcasts. Start your

26:01

day with us. Here

26:07

is the second half of

26:09

Jesse Wente's talk at the

26:11

Imagining 2080 Forum at McMaster

26:13

University. The writer

26:15

and arts administrator envisions a better

26:17

future for all, built on Anishinaabe

26:20

ways of being. That's

26:22

because he thinks that our current

26:24

systems are clearly harming us. But

26:27

he sees solutions if

26:29

we can develop a different relationship

26:32

with time. That's

26:34

why he's called the talk, Remembering

26:36

Our Future. For

26:43

those that have suffered the most under colonization,

26:45

I do think we tend to

26:47

have these memories closer at hand. It's

26:49

why I agree to do these sorts of

26:51

talks, why I do all this work.

26:54

Because again, I'm honoring my great

26:56

grandparents here. This is what

26:58

they wanted me to be doing. And so this is what

27:00

I am doing. And

27:02

then the other thing I would say

27:05

in terms of because there was a lot of

27:07

conversations around hope in my session and

27:09

around how we hope. And

27:11

I guess is here,

27:13

here's what I say around hope

27:16

as a First Nations person and as a person

27:18

who's been, if you know anything about my career,

27:20

deeply critical of this place and its systems and

27:22

all of that sort of stuff. But

27:25

I believe in Canada in the end. And

27:29

how could I say that, considering how it's done

27:31

to my family and all that stuff. And

27:34

the reason I believe in Canada is because Alex

27:36

and Maggie believed in Canada. That's

27:39

why they prepared. They

27:41

didn't prepare just for their community. It was a

27:43

preparation for this new nation that they understood that

27:45

they were a part of. They

27:48

were preparing so that I would be here

27:50

to do this for you. Because

27:52

they understood that this was going to

27:55

be necessary. They understood that the

27:57

systems that they were going to be

27:59

gathering weren't. going to be sustainable

28:01

systems. So

28:03

they understood that we were going to have

28:05

to. This is why we have the seventh

28:08

prophecy, that prophecy, is we had a deep

28:10

understanding that we would have to come back

28:12

to here, that you would end

28:14

up asking us to come

28:16

in your spaces of learning to

28:18

talk about this. Because you need,

28:21

you needed to tap back into this knowledge. So

28:23

they preserved it for this moment, for

28:26

this moment going forward. So

28:28

the reason I hope is because they sacrificed

28:31

so much to make

28:34

sure that we could be here and they believed

28:36

in Canada that

28:38

it worries me that Canadians don't believe it as

28:40

much as those that have been hurt the most

28:42

by it. First

28:44

Nations people have sacrificed more for this

28:46

country than any other community. We

28:49

have given everything to this

28:51

country. I think what

28:53

we need to demand or what we want back from

28:55

the future of this country is

28:57

for that to be worth it. That's

29:01

the challenge I would say to everyone here is

29:03

how can in 2080 we

29:06

could you make it worth it to my family for

29:08

everything we have gone through? I

29:11

have an idea about how you could

29:13

do that. When

29:15

my grandmother went into her school, my grandmother

29:17

started attending St. Joseph school for girls in

29:19

1933 when she was six years old. So

29:22

when my grandmother went into the school, she only

29:24

spoke Anishinaabe Mowin. Right, the

29:26

family only spoke our language. When

29:29

she came out, she never really spoke the

29:31

language again. Okay? So that's

29:33

why I grew up in English. That was

29:35

two generations ago. What

29:37

if we thought of

29:39

that two generations from now, which

29:43

is actually before 2080, believe it or not,

29:45

so we wouldn't even get there. But what

29:47

if we could imagine that in

29:49

two generations my

29:52

family will be fluent again? Could

29:54

we imagine that? Because

29:57

when I was asked one of the prompts I was given for this

29:59

was sort of imagine,

30:02

vision, what does 2080 look like? And

30:04

the first thing that came to mind was actually wasn't

30:06

a vision, it was a sound for

30:08

me. And

30:10

the first thing I heard was this conference in 2080.

30:14

And it was entirely an Anishinaabe moment. Everyone

30:18

here, everyone, not

30:20

just the Anishinaabe, everyone spoke

30:22

our language. They have these

30:24

discussions in our language, which

30:27

is a very different one than English.

30:30

It sees the world very differently.

30:32

It doesn't really have possessions in the same way

30:34

that English does. It doesn't

30:36

really even have verbs. It has states of being our

30:39

language, right? And

30:43

why is that to me maybe the most hopeful future?

30:46

Well, one, I think it's incredibly achievable.

30:49

Like, so achievable, I had dinner with a

30:51

guy the other night who could achieve it. He's

30:54

an Anishinaabe language teacher. He's already developed

30:57

a system that's being used at universities

30:59

all throughout the region. I

31:01

said, could we have our communities be fluent

31:03

by 2080? And he's like, we could have it by

31:05

2050. Now,

31:09

if everyone here could speak our language,

31:12

then we could start to talk about the worldview. We

31:15

could start to understand our relationship to this place

31:17

and each other in a very, very different way.

31:20

Right? Because one of the first vision I

31:22

had when I thought of 2080, and

31:25

I heard a lot of conversations around, you

31:28

know, the 2080 I envision is for my

31:30

children, which is great. I

31:32

mean, I have teenagers. I guess

31:35

they'll still be around in 2080. I don't know. But

31:38

that's not who I envisioned it for, to

31:41

be honest. I envisioned

31:43

2080 for the tree in

31:45

the lake, who

31:48

are also my kin. I

31:52

envisioned what it would be for them to

31:55

be at the table, as we like to say, with

31:57

the rest of us. What would that look

31:59

like? And here's the thing, I think

32:02

that vision, I think the language

32:04

came to me first, because that vision

32:06

is best seen in Anishinaabe Moen. English

32:11

doesn't do well with the idea of the land because

32:13

it wants to possess it. Anishinaabe

32:15

Moen has no such ideas

32:19

in it. We understand that the land

32:21

possesses us, so it's very different. And

32:23

so in that rubric, the idea that we would

32:26

plan for the future means that actually we steward

32:28

the land in a very different way. The

32:32

thought experiment I usually use for this

32:34

is ask people to think about

32:36

the difference between a mountain and

32:38

the train that goes around the mountain. What

32:41

is more real? The

32:43

mountain or the train? I

32:47

would suggest that the mountain has seen a

32:49

million modes of transportation passed by its

32:53

history, and it knows that the train is

32:55

just the latest. The

33:00

mountain is the lake, the

33:02

air, the sky. They're

33:04

more real than anything we can do. And

33:08

Anishinaabe Moen centers that for

33:10

us. It centers us in a place of

33:12

humility and understanding. No matter what I

33:15

can do or say to you today, the mountain will still be

33:17

more real than it. Because

33:19

it'll be here long after my words have

33:21

left. It will always be here.

33:24

And for us, one of the things we

33:26

need to deeply remember is what

33:29

it is to live in a

33:31

similar timeline to the mountain. If

33:34

you understand what I mean. Which is

33:37

to say that if you think of the mountain and you

33:39

think of us in relation to the mountain, well

33:41

the mountain is going to be here way longer than

33:43

us. It was here way before us. So what is

33:45

our relationship to it? Who cares for who in that

33:49

situation? Does the

33:51

thing that's going to be here forever care for the thing that's

33:53

only going to be here a short time? Or

33:56

does the thing that's going to only be here a short time, are

33:58

they obligated? to care for the thing that's going

34:01

to be here forever. And of course

34:03

the answer is that one. We

34:05

are obligated to care for our relations

34:07

because they are going to outlive us.

34:10

And why should we think that they should

34:12

care for us when we are going to be

34:14

here like that? So

34:17

we need to deeply remember what

34:19

it is to live in

34:22

that way. And so in that deeply

34:24

remembering, we can

34:27

actually build the future. We can

34:29

imagine a future that is utterly

34:32

different than when we are. And I

34:34

would encourage us not to be precious

34:38

around the things that we have constructed to

34:40

support and instead focus, like my

34:42

great grandparents did, on what is most important

34:44

to preserve in this moment. Is it the

34:46

building or the systems? I'm

34:49

gonna say it is not. It is

34:51

not those things. The most important

34:53

things to preserve are the human things, how

34:56

we communicate, how we live, how

34:58

we understand the world, how we

35:01

dance and share with one another.

35:03

Those are the things that no matter what happens,

35:05

no matter the venue, because remember the round dance,

35:07

we used to do it outdoors. We can do

35:09

it inside now. It's

35:12

not about the venue. It's not about

35:14

the where, the construction of things. It's

35:16

about those most human

35:18

things. So if we were to think now

35:20

in that sense, what is it that

35:23

we want to preserve? What

35:25

is it that is most dear that we protect?

35:27

Is it the systems or is it

35:29

how we live together? Is

35:33

it the government that's only been here a

35:35

short time? Or is it the

35:38

idea of no, it's community relations, right

35:40

relations is the way we would put

35:42

it, should govern us. It's

35:45

really deciding what it is

35:48

that we will need in 2080 and

35:50

protecting that in these moments. And

35:52

what I'm suggesting is none of it

35:54

is the tangible stuff, none

35:57

of it. It's all the intangible stuff. And

35:59

it may recover. require that

36:01

we hide things, that

36:04

we put things away, that we

36:06

keep the one kid home for

36:09

this moment and we teach them

36:11

something different. There's a lot of

36:13

talk about kids in the future. One

36:17

of the things to consider is that maybe some

36:20

folks from outside our community, maybe now's the

36:22

time, maybe we've come back to a time

36:24

where we need to keep the one kid

36:26

home to teach them something different. Yeah,

36:29

we need a bunch of the kids to know

36:31

how to do world changing. We will also need

36:34

a lot of kids to be able to remember

36:36

what it was, to

36:38

remember all of this. So

36:41

is that what they're getting in the schools or is there a

36:43

different venue for them to learn? And should

36:45

we be scared if they're not going to get an

36:47

education? What is a BA going to mean

36:49

in 30 years? Have you thought about that? Why

36:52

are we so clinging to that? What's

36:56

important? And let's cling to that, like

36:58

my great grandparents did and

37:01

like our communities did. Because I

37:04

dream of a future for the trees, for

37:06

the water, for my non-human

37:08

kin. I dream

37:10

of a future where Canada means

37:12

something very, very different and acts

37:15

very, very different. It's the vision

37:17

my grandparents had of this place. One

37:20

of shared humanity,

37:22

shared resources of learning from

37:25

one another. Because they always thought

37:27

that yes, they would send their kids to school to learn

37:29

from this new world. They

37:31

always knew you'd come calling back to have me come

37:33

back so you could learn from the old one. So

37:38

what I really want to encourage is

37:43

that this deeper membrane, that the future

37:45

we want has already existed in the

37:48

past. We just have to dig into

37:50

our memories to remember it. Then

37:52

we have to remember what it was to build

37:54

that and start doing

37:56

that action now. And

37:59

we don't need to rely on

38:01

the institutions or systems or governments

38:03

or any of that to do

38:05

any of this work. My community

38:08

did it in exact opposition to

38:10

those forces, right? They didn't

38:12

get permission from the government. They would have been

38:14

arrested if they had been known they were doing

38:16

this, right? That was real

38:19

resistance. That was saying

38:21

we're gonna plan for the generational

38:23

future of our community against

38:25

the wishes of the most powerful.

38:29

Outside of the systems meant to

38:31

control us. We

38:33

are no different than them. We're

38:36

the same. We can do the same now. And

38:39

I think we should do the same now.

38:41

Because we're at a moment, we see it all over the

38:43

world. It's this, it feels all

38:46

tense and it

38:48

feels precarious. It

38:50

is. But again, we have

38:52

been here before. We

38:55

will get through this. What

38:57

we need to is at this moment protect what

38:59

is most key

39:01

for our future and

39:04

to remain hopeful. Because

39:06

I don't think we can live without

39:08

hope. Hope is literally the only

39:10

thing that allows us to live, I

39:13

think, other than air and water. And

39:15

I hope for them that we'll still have them. But

39:19

I think if we can

39:21

remember deeply, we can

39:23

recall that where we are now

39:25

is both familiar. And

39:28

in that familiarity, we

39:30

can figure out how we survived it and

39:33

how we move forward. I

39:35

want to stop there. But I

39:37

will say in my language, for

39:42

listening, I say it four times to

39:44

acknowledge all four directions. And I want

39:46

to thank you very much for

39:49

having me here today. It's been a real privilege. Our

40:01

Future by writer, broadcaster, and

40:03

arts administrator, Jesse Wente. Thank

40:06

you to Kaylee Wiseman, Anne

40:08

Elizabeth Sampson, and the organizers

40:10

of the Imagining 2080

40:12

Forum at McMaster University. I

40:15

had the opportunity to connect with Jesse

40:17

Wente again in the aftermath of his

40:19

talk. You

40:22

talk in your lecture about the

40:25

deep responsibility that you feel around

40:27

helping your community and being one

40:29

of its voices in the wider

40:31

society, as your great-grandparents had intended.

40:35

Do you remember when you

40:37

first felt that responsibility profoundly

40:39

growing up? Yeah,

40:41

I mean, I remember a conversation my mother

40:43

and I had. It was

40:45

probably around about the time I started

40:48

attending a private school,

40:50

a private boys' school here in Toronto.

40:54

You know, I think the way my

40:56

mom framed it was that I

40:59

was currently and going

41:01

to lead a more privileged life than

41:05

many in my family and many in my

41:07

community. And that with

41:09

that privilege came an obligation

41:12

to turn back to my

41:14

community once I

41:16

had sort of accrued enough experience

41:20

to make it, you know,

41:22

learned as much as I possibly could to then

41:25

bring that knowledge back to help

41:28

my community as best I could. And that's

41:31

very much, I think, the same message

41:33

she received. And it's,

41:35

I think, very much what my

41:37

great-grandparents, Alex and Maggie Miyawasagi, what

41:39

they were, what they

41:41

sort of had in mind in terms

41:44

of the direction of the family. So

41:47

I think that's, you know, I think that's the

41:49

sort of lineage. And that's

41:52

probably the first time that I became aware that I

41:54

was, you know,

41:56

that there was a circle there that needed

41:58

to be made whole at

42:01

some point. Yeah. I wonder

42:03

from that point onwards, Jesse, whether you

42:05

ever felt that responsibility

42:07

feeling heavy. Yes.

42:15

Yes. I think in

42:17

recent years, I have

42:20

found it maybe too

42:22

heavy at times. Now,

42:25

some of that is self-imposed

42:28

in terms of

42:30

my own thinking

42:32

and feelings

42:35

and sort of navigating and what

42:37

some of that has just felt like. So

42:39

I don't know how much of

42:41

that is real, but then some of it is just real.

42:44

And I don't think I'm

42:46

alone. I think anyone who, however

42:50

they come about, it takes

42:52

on sort of leadership positions,

42:55

especially for communities that have

42:57

been forcibly marginalized

43:00

or gone through what

43:02

my community has gone through. I think there's a lot

43:05

to be done and there's a lot of pressure

43:07

that you can put on yourself to

43:11

do as much of it as

43:13

you can. And where I am

43:15

at this point in my life, I would

43:17

say, I'm beginning to

43:21

heal, I guess, from some of

43:23

the efforts that it took to try

43:27

to assist my community in the

43:29

best way that I could. And

43:33

for me, that meant often

43:36

being in colonial spaces and in places

43:39

that were sometimes hostile to our existence.

43:41

And so that

43:44

has taken its toll, I

43:46

would be the first to admit. So yeah, I

43:49

think that burden can be hard. But one of

43:51

the things I've learned, certainly

43:53

through this journey, is that one

43:55

of the key things

43:58

about leadership is when to know to stand up for the people. step

44:00

back when to make space for

44:02

other leaders to do some of that

44:04

work, and also to recognize that

44:06

we sit in circle at a drum with

44:08

each other. And if we

44:11

are all beating the pulse, it

44:14

can be okay if one of us holds

44:17

their drumstick back for

44:19

a little bit and takes that space

44:22

for themselves to take a break, because

44:24

others will continue to

44:26

beat the drum. So that's a lesson that I've

44:28

also learned. But yeah, it

44:31

has not been without its challenges. I

44:34

can only imagine the

44:37

weightiness of being told that, especially as

44:39

a young man. When you

44:43

think back to that time, were

44:45

there moments in that early phase

44:47

of your life that you

44:50

recall that really cemented that sense

44:52

of cultural mission for you? Like,

44:54

is there an example that you can give? What

44:57

may be a specific example? It

44:59

was something that came over time,

45:02

some of my time when I was at

45:04

CBC, and just realizing

45:06

that my community,

45:10

meaning Anishinaabe folks, or if you want to

45:12

take it larger, First Nations folks,

45:15

that we

45:18

weren't present

45:22

in the creation of storytelling in

45:27

this place, both in terms of telling

45:30

stories, but also in

45:32

terms of being thought of as people who

45:34

might receive stories, who

45:36

might take them in. In those early days,

45:38

it felt often invisible

45:44

and forcibly made

45:46

so. So the

45:49

lack, I

45:52

was a film critic for so many years now. I

45:56

was someone who watched when I was a film

45:58

critic and I was working at film festivals and

46:00

doing all that curation. You

46:02

know, I was watching 1,500 movies a year, and

46:05

I did that for 20 years. Wow.

46:09

Right? Now, I'm

46:11

watching all of these stories, and

46:15

especially until relatively very

46:17

recently, right? The

46:19

vast majority of that time, I'm not seeing stories

46:23

that reflect me or my community,

46:25

or are my broad community, like,

46:27

they're just not there. They don't

46:29

exist. And I'm

46:31

having to interact with all

46:33

these other stories. And

46:36

it just became a sense of, well, I

46:38

really wanna see some things that

46:41

feel closer to me. I

46:43

wanna be able to feel about a movie or

46:45

a story the

46:48

way I know other communities do when they

46:51

get to see themselves reflected. I wanted to

46:53

move closer to the decisions of what films

46:55

get made, who gets to make movies, like

46:58

who gets to tell stories, like how does that

47:00

work? And

47:03

so that became a very intentional sort

47:05

of thing. And luckily, it's a path that

47:07

many before me have taken, and

47:12

we were able to just build on that. So

47:14

I think it was not necessarily

47:16

one incident. It was

47:18

more just this feeling

47:21

of absence during my day-to-day

47:23

work. Yeah. Moving on

47:25

to the ideas that you addressed in

47:27

your talks, specifically, I wanna

47:31

talk a little more about the

47:33

Anishinaabe way of seeing time. Why

47:37

is the far future such

47:41

a big consideration in that

47:43

way of thinking? I

47:46

would, you know, there'd be more

47:49

learned people than me to ask about

47:51

that, Anala, but from my understanding, it's

47:54

because of the land. So

47:56

I think, so what... What

48:00

I would say is like an understanding

48:02

of time as experienced by the land,

48:05

as opposed to as experienced by humans. Right.

48:08

Because we have a very different experience of

48:10

time, just like we have a very different

48:12

experience of time of like animals, a fish,

48:15

or a bird, or an insect that

48:17

may only live for 24 hours, right? That's

48:20

whole life cycle, right? And what we would call

48:22

a day, but for its life,

48:25

right? So there's all sorts

48:27

of different experiences of time.

48:30

And I think the notion

48:33

of that elongation or that sort

48:35

of future is an acknowledgement that

48:37

the land, right, exists

48:39

in a time that

48:41

we actually really struggle,

48:43

especially currently. But

48:47

like, I think humans in general, because we don't live

48:49

in the same sort of understanding

48:51

of time as the land. And

48:54

I think for a lot of First Nations,

48:56

and certainly my understanding of Anishinaabe, part of

48:58

the goal is to try to align the

49:00

land has. And if you're the land, so

49:02

if we think of a mountain or a

49:04

lake or an ocean, what does

49:08

it really consider a month to

49:10

be? Exactly. What

49:13

does it consider one of our

49:15

lifetimes to be to it? Like

49:18

not much, right? Like very minimal. And

49:21

if you ground yourself in sort of that

49:25

sense of time, then

49:29

what we're doing here, like

49:32

what we're supposed to be doing and

49:34

what our obligations and responsibilities might be

49:36

to both time and the things that

49:39

sustain us here in our

49:41

existence here, I

49:44

think shifts a bit, right? I

49:46

think one of the challenges we

49:49

have globally and certainly here on these lands

49:52

these days is we exist. We

49:54

want to make everything exist in human time,

49:58

right? We want everything. we want to bend

50:01

it to us. And, and the

50:04

reality is that's sorta

50:06

not how the land works. Right?

50:08

The land doesn't understand

50:11

that. And we can see that. We see the

50:13

evidence of that all over the place. Um,

50:16

and so I think more and more for

50:19

Anishinaabe, but also just humans in general, cause

50:21

I don't think it's distinct on Anishinaabe, this

50:23

understanding. I think it's just

50:26

an older understanding. The more

50:28

we can grasp our responsibilities in

50:30

the time that the land understands,

50:32

uh, which would mean that we

50:34

are not the center of it.

50:36

And, and if we were, if

50:38

we situate ourselves then, well,

50:40

what should we be thinking about how we approach, you

50:42

know, the, the, the McMaster talk was about this idea

50:45

of 20, 80, right? Which

50:47

is what, 55

50:49

years, I guess, 56 years from when

50:51

you and I are speaking. Again,

50:54

if I think of this from the land's

50:56

point of view, that's tomorrow. Probably

50:58

not even that's like later this

51:01

hour, if not

51:03

five minutes from now. That really shifts the

51:05

way you look at things, doesn't it? For me,

51:07

it, it, it does. And

51:09

it shifts the, it shifts

51:11

what we should

51:14

be up to like what, what we

51:16

should be thinking around how

51:18

we exist together and what we

51:21

should be. Doing,

51:23

and it puts into context some

51:26

of the challenges that we face, right?

51:30

It doesn't make them easier to be honest,

51:32

right? If we think of them, it makes

51:34

them, it makes them what they are. Um,

51:37

but it also gives us a sense that

51:41

whether we face them or not, the

51:45

time of the land will

51:47

continue. And so that

51:49

I think should give

51:51

us all the impetus to

51:54

start moving in

51:56

a different way to

51:58

come more and more. alignment with

52:00

that because shouldn't humans want to

52:03

exist in the same way that

52:05

the land does forever? You

52:08

even say in your lecture that

52:10

even non-Indigenous people without those

52:13

memories of the past have access

52:15

to that deep remembering. Can

52:17

you tell me how? Sure. I

52:20

think it just requires a deeper

52:23

journey into your

52:25

own memory, into your own

52:27

past, into your own understanding

52:29

of time. And

52:32

the reason I say that is because for First

52:35

Nations people, my community, it's not that long ago

52:37

that I can talk to my mom and hear

52:39

about some of the old ways. My mom. This

52:43

is not all... It's very

52:45

close. For, I think,

52:47

lots of other people, it's more distant to

52:50

remember before this, right? And

52:53

for some, they may remember

52:55

other systems that were just as bad

52:57

or it may take even longer

53:02

to find freedom, to find

53:04

that space where you can

53:07

truly remember what

53:09

it was to be fully

53:11

human and not beholden to systems,

53:13

but rather have systems that serve

53:16

you in the land, right?

53:20

And we have in that remembering, maybe

53:23

as far back as you may have to go to

53:26

find that place, it's probably

53:28

worth noting the length of that journey

53:30

and all of the barriers that separated

53:33

you from that. Because

53:35

that might give you the indication of the systems

53:37

that are, A, collapsing,

53:40

right? That we talked about earlier. And

53:42

also the systems that we may not want

53:45

to regenerate, that we may want to seek,

53:47

that that's the solution we're actually seeking for in

53:50

the past, is what was before. What

53:52

can we rely on before? And how can that then

53:55

inform what the after? How

53:57

can that help us construct? and

54:00

plan for the after

54:02

that we all want, and the after

54:04

that will bring us closer

54:08

to the understanding

54:11

of this place that the land

54:13

has for itself. Writer,

54:20

broadcaster, and arts administrator

54:22

Jesse Wente. His memoir,

54:24

published in 2021, is called Unreconciled

54:28

Family, Truth, and Indigenous

54:31

Resistance. This

54:37

episode was produced by Lisa Godfrey.

54:41

Web producer for Ideas is Lisa

54:43

Ayoosso. Technical producer,

54:45

Danielle Duval. The

54:47

executive producer of Ideas is Greg

54:50

Kelly, and I'm Nala Iyad.

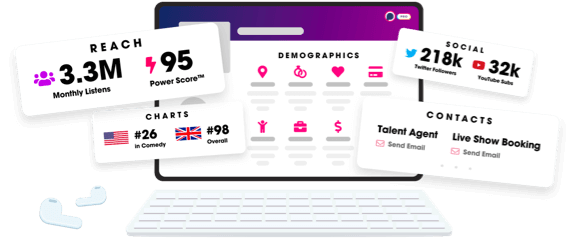

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us